Binderising Exercises from the Doing Data Science Book

Introduction

I’ve been going through the Doing Data Science : Straight Talk from the Frontline book by Cathy O’Neil & Rachel Schutt published by O’Reilly Media and working through the exercises in Julia. I’ll keep this post updated as I work through it and post more examples. I have written the code in notebooks using nteract. As I was going through the exercises I found a tutorial on how to generate a Binder from notebooks, and I thought it might be a good idea to try this out as well. I’ve briefly outlined how I did this below, before going through each of the exercises I did very quickly.

Binder

Binder “allows you to create custom computing environments that can be shared and used by many remote users”. Essentially it allows you to build an online Docker image of a GitHub repository, which seems like it could be very handy for teaching or sharing code from a publication, etc. There is a tutorial on how to go from “Zero-to-Binder” in Python, R, and Julia provided by the Alan Turing Institute.

I followed the Julia tutorial which is relatively straightforward however did provide a few hurdles to overcome along the way! Firstly I created a repo from my Doing Data Science notebooks, rather than create a new hello, world script. The first thing I did was open up my JuliaPro IDE and change directory to my repository. I entered the package manager by pressing ] and typed in activate .. I executed the following

add DataFrames, Gadfly, Queryverse, Statistics, Dates,Statistics, Random, Plots, GLM

which generates the Project.toml and Manifest.toml files which contain the dependencies that I’ll be using. To the Project.toml I also added

[compat]

julia = "1.4"

to ensure I’m using the same version of Julia in my Binder. I then attempted to build my first Binder, which failed! The errors pertained to some dependencies failing, in particular it could not find the correct versions of some packages on GitHub that matched the versions I have installed on my machine. In particular, this failed for the BinaryProvider and GR packages. To get around this issue I had to add the latest versions of the packages to my project using the following.

add https://github.com/JuliaPackaging/BinaryProvider.jl

add https://github.com/jheinen/GR.jl

The next issue (fortunately also the final issue!) was related to the PyCall package that was being used by some of the dependencies. In particular, the Excel Reader in QueryVerse was calling the xlrd Python package, however this could not be found by the Binder. This issue can be solved by creating a requirements.txt, which lists the Python dependencies required, and entering the following.

xlrd==1.1.0

Further Python packages can be included in the same manner. After including this file the Binder compiled with no problems, although it did take quite a long time! The link to Binder for the entire repo can be found here:

Links to each individual notebook are also given at the beginning of each section below.

Chapter 2 - Exploratory Data Analysis

Binder Link:

Note: Prior to running the first cell you have to ensure that the Kernel is set to Julia rather than Python.

The first exercise in the book is to perform some basic Exploratory Data Analysis(EDA) on New York Rolling Sales data containing housing sales data over a 12 month period. The data can be downloaded here and specifically I will be briefly looking at the rollingsales_manhattan.xls data.. I imported the data using QueryVerse.jl which is a meta-package containing a number of packages useful for data analysis. I have some experience of using Pandas in Python and there is a reasonable amount of overlap with the functionality used by QueryVerse so that made things a little bit easier when getting started.

The first thing I noticed when exploring the data was that DataFrames uses first(n) rather than head(n) to print the first n rows of the dataframe (you can use head however this is now deprecated).

One useful thing I learnt was how to use the Data Pipeline method in Query using the |> operator, allowing for a number of operators to be performed sequentially on the dataframe. This includes filtering, grouping, mutation, mapping and more - the docs can be found here. An example of this is plotting the proportion of properties that were sold (i.e. a sale price of greater than $0) in each neighbourhood. I achieved this using the following

D |> @groupby(_.NEIGHBORHOOD) |> @map({Key=key(_), Count=length(_),PropSold = sum(_.SALEPRICE .>0 )./length(_)}) |> @orderby_descending(_.PropSold) |> @vlplot(:bar,x={:Key,sort="-y"},y={:PropSold})

by grouping the data by neighbourhood, creating a new column which contains the proportion of properties sold in that neighbourhood, ordering them, and plotting them as a bar chart. The @orderby_descending(_.PropSold) command is not required for the plotting as the x={:Key,sort="-y"} ensures the data is ordered in the plot, however I kept it in case I wanted to print it out to a line when testing.

The rest of the notebook explores the sale prices of the properties for different property types across time and neighbourhood - In particular it looks at Family Homes and Apartments. When looking at the data there was some clear differences between neighbourhoods, for example the median sale price in Harlem Central was 383persqfforafamilyhome,comparedwith2177 per sqf in Greenwich Village West. There did not appear to be any change of price over time (only 12 months of data was provided) however there was a large spike in sales in December which can be seen in the plot below. I was unsure why this might be the case, I was wondering if some of the dates had been automatically set to the end of the year but this did not appear to be the case. Perhaps there is some tax reason for this? Check out the notebook for my analysis at the link at the start of this section.

Chapter 3 - Basic Linear Regression

Binder Link:

Note: Prior to running the first cell you have to ensure that the Kernel is set to Julia rather than Python.

The second exercise I attempted was the basic linear regression exercise in Chapter 3 of the book. The outline was to simulate some data, add noise and then try to recover the coefficients using linear regression.

The exercise starts by generating a single independent variable and a single dependent variable and performing a linear fit to show that the fit coefficients are returned almost exactly when Gaussian noise is added to the variables, before simulating different distribution and increasing the number of variables. I also split the datasets into training and test datasets of varying sizes to explore how the Mean Squared Error(MSE) varies with the size of the sets. I performed the fitting using the GLM package which was straightforward, a linear fit was performed using:

Data = DataFrame(X = x,Y = y);

model = lm(@formula(Y ~ X),Data)

One of the main learning points for me was to explore different plotting techniques and how to generate subplots. One of the major challenges was to generate a 4x4 grid of plots, where the plots on the diagonal contained histograms of the single variables and the plots off the diagonal were scatter plots showing the relationship between each pair of variables. When I was writing the notebook I was unable to do this using the standard functionality as it would only let me input up to 10 plots in a single subplot, so I delved further into the docs and found out how to generate my own userplot. To do this I first define a new userplot and define a recipe for my new type of plot. The recipe contains information about the layout of the plots and what type of plots they will be. I was able to do this for my 4x4 case, however ideally I’d like to generalise this to any number of variables. This is on my todo list! For now, I’ve included my code below and the image below that as well.

@userplot CompPlots_4x4

@recipe function f(h::CompPlots_4x4)

if length(h.args) != 5 || !(typeof(h.args[1]) <: AbstractVector) ||

!(typeof(h.args[2]) <: AbstractVector)||

!(typeof(h.args[3]) <: AbstractVector)||

!(typeof(h.args[4]) <: AbstractVector)

error("CompPlots_4x4 should be given four vectors. Got: $(typeof(h.args))")

end

x1,x2,x3,x4,labs = h.args

legend := false

link := :none

framestyle := [:axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes :axes]

grid := true

layout := @layout [hist scatter scatter scatter

scatter hist scatter scatter

scatter scatter hist scatter

scatter scatter scatter hist]

# first histo

@series begin

seriestype := :histogram

subplot := 1

title := string(labs[1], " Hist")

x1

end

# second histo

@series begin

seriestype := :histogram

subplot := 6

title := string(labs[2], " Hist")

x2

end

# third histo

@series begin

seriestype := :histogram

subplot := 11

title := string(labs[3], " Hist")

x3

end

# fourth histo

@series begin

seriestype := :histogram

subplot := 16

title := string(labs[4], " Hist")

x4

end

# x1-x2 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 2

title := string(labs[1]," - ",labs[2])

x1,x2

end

# x1-x3 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 3

title := string(labs[1]," - ",labs[3])

x1,x3

end

# x1-x4 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 4

title := string(labs[1]," - ",labs[4])

x1,x4

end

# x2-x1 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 5

title := string(labs[2]," - ",labs[1])

x2,x1

end

# x2-x3 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 7

title := string(labs[2]," - ",labs[3])

x2,x3

end

# x2-x4 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 8

title := string(labs[2]," - ",labs[4])

x2,x4

end

# x3-x1 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 9

title := string(labs[3]," - ",labs[1])

x3,x1

end

# x3-x2 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 10

title := string(labs[3]," - ",labs[2])

x3,x2

end

# x3-x4 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 12

title := string(labs[3]," - ",labs[4])

x3,x4

end

# x4-x1 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 13

title := string(labs[4]," - ",labs[1])

x4,x1

end

# x4-x2 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 14

title := string(labs[4]," - ",labs[2])

x4,x2

end

# x4-x3 scatter

@series begin

seriestype := :scatter

subplot := 15

title := string(labs[4]," - ",labs[3])

x4,x3

end

end

Some tweaks are needed on the plotting, in particular the limits need changing slightly as some of the scatter points are slightly cut off and the x ticks may also need some editing. The rest of my analysis can be found in the notebook.

Chapter 3 - Basic Machine Learning

Binder Link:

Note: Prior to running the first cell you have to ensure that the Kernel is set to Julia rather than Python.

Chapter 3 then leads on to an example of implementing a couple of basic ML algorithms on the Manhattan rolling sales data: Linear Regression and K-Nearest Neighbours. We start with trying to predict the sale price using the total area of the properties, before introducing a number of other features to predict the price including neighbourhood, building type, etc.

To perform the Linear Regression I used the MLJ package, which provides a common interface for a number of machine learning tools. In particular it brings together a number of models from a wide range of packages. The nice thing about MLJ is that it automates a lot of the processes for you, for example instantiating the model and then evaluating it will perform cross-validation, here’s my code for a simple regression model.

D_fam_sub = D_fam |> @map({X = log(_.GROSSSQUAREFEET),Y = log(_.SALEPRICE)}) |> DataFrame

y,X = unpack(D_fam_sub,==(:Y),==(:X);:X=>Continuous,:Y=>Continuous)

X = MLJ.table(reshape(X,291,1))

@load LinearRegressor pkg="MLJLinearModels"

model = LinearRegressor(fit_intercept = false)

LR = machine(model, X, y)

rsq(y_hat,y) = 1 - sum((y .- y_hat).^2)/sum((y.-mean(y)).^2)

evaluate!(LR,measure=[l2,rms,rmslp1,rsq])

Introducing more variables improved the prediction model, however problems were introduced when using the neighbourhood. For example, some of the residuals were very large when fitting on the test data. This may have been caused by the low number of data points belonging to certain neighbourhoods. One way of overcoming this may be to combine neighbourhoods to larger geographical areas to increase the number of data points. In order to introduce the neighbourhoods into the model, I converted the feature to a Multiclass categorical variable and used one-hot encoding.

coerce!(X,:X2=>Multiclass)

schema(X)

hot = OneHotEncoder(ordered_factor=false);

mach = fit!(machine(hot, X))

X = transform(mach, X)

schema(X)

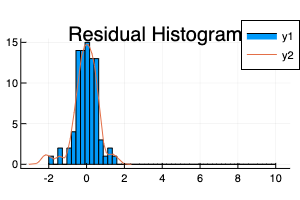

This code converts the variable X2, which was my neighbourhood variable, to a Multiclass and then implements the one hot encoding. A residual histogram is given below, note that the residuals are the log values as the outcome variable was the log of the sale price.

The second part of the exercise uses a K-Nearest Neighbours classifier to classify the neighbourhood based on the latitude and longitude values. K-Nearest Neighbours is a simple algorithm and I have used it before, however the challenging part of this exercise was to get the coordinates and clean the data to ensure the coordinates were correct.

The first step was to clean the address values, many of which contained a large amount of white space. This can be performed easily using Query.jl.

D_sub = D_sub |> @mutate(LONGADDRESS = replace.(_.ADDRESS," " => "")) |> @mutate(LONGADDRESS = string(_.LONGADDRESS,", New York, NY, ", Int(_.ZIPCODE), " US")) |> @mutate(LONGADDRESS = replace.(_.LONGADDRESS," , " => ", ")) |> DataFrame

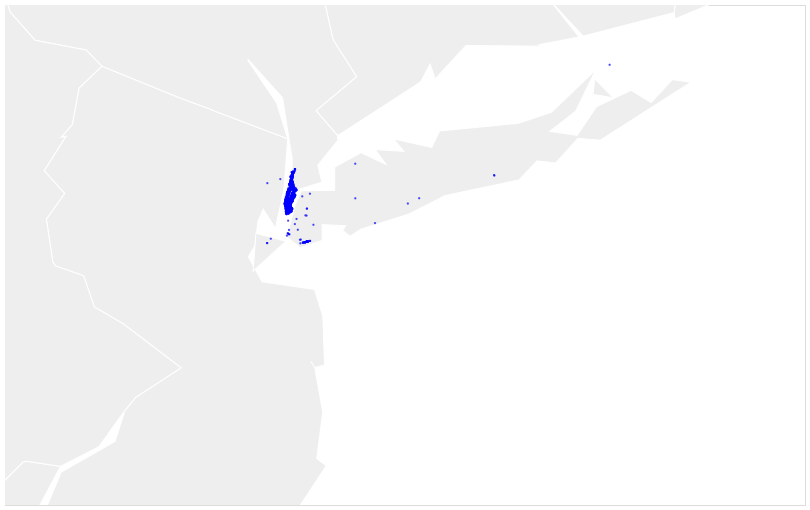

This code replaces double white spaces with single spaces, adds in the city, state, and zip code to the address and removes any white space prior to commas. Subsequently, I had to get the coordinates of the addresses, and to do this I used LocationIQ. You can sign up for a free API key on their website, however this restricts you to 60 requests per minute. For my 1450 addresses, this took over 30 minutes but I just left it running in the background. There may be other, faster, alternatives to getting the coordinates. I then mapped the coordinates to check that the coordinates were okay, and found that some of them were outside of Manhattan. To map the coordinates I used the us-10m dataset from VegaDatasets, which contains the state boundaries at the 1:10,000,000 scale. To set the parameters of the map I used the Vega Projection Editor which was very handy!

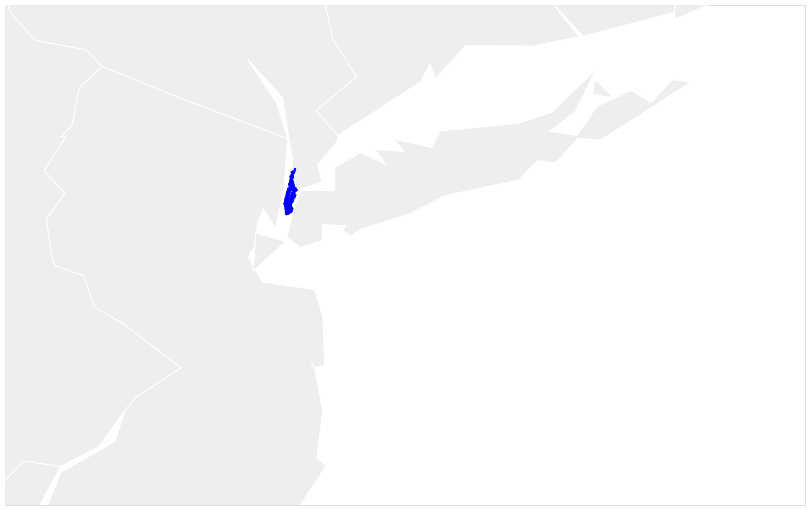

Some of the coordinates were in upstate New York and others were close to Manhattan but not quite on the island, so I had to figure out how to filter these data points out. To do this I downloaded the boundary of New York City Boroughs from NYC OpenData (It is important to note here that the boundary is defined by 34 separate polygons as Manhattan includes a number of islands - e.g. the Statue of Liberty is on Liberty Island which is included as a separate polygon). I then used the Luxor package to check whether each set of coordinates returned by LocationIQ was inside of the boundaries.

using JSON

borofile = open("Borough Boundaries.geojson")

headers = JSON.parse(read(borofile,String))

println(headers["features"][3]["properties"])

manh_boundary = headers["features"][3]["geometry"]["coordinates"]

D_adds[!,:MANHATTAN] = falses(size(D_adds)[1]);

nrs = size(D_adds)[1];

using Luxor

using ProgressMeter

@showprogress for region in manh_boundary

bnd = [Point(p[1],p[2]) for p in region[1]];

for i in range(1,stop=nrs)

coord = Point(D_adds[i,:LONGITUDE],D_adds[i,:LATITUDE]);

isin = isinside(coord,bnd);

if (isin==true)

D_adds[i,:MANHATTAN] = true

end

end

end

I then filtered out those addresses that lay outside of the Manhattan boundary. Here’s a map of the coordinates before…

… and after filtering out the coordinates.

… and after filtering out the coordinates.

Implementing the KNN was relatively straightforward following this, and I tested out how changing the value of k affects the accuracy. Unfortunately, the API licence restricts the caching of the coordinates so I have not saved them to the notebook. You will also need to download an API key to run the notebook.

Implementing the KNN was relatively straightforward following this, and I tested out how changing the value of k affects the accuracy. Unfortunately, the API licence restricts the caching of the coordinates so I have not saved them to the notebook. You will also need to download an API key to run the notebook.

Chapter 4 - Naive Bayes

A separate post on Naive Bayes is coming shortly!

Chapter 5 - Logistic Regression

Chapter 5 introduces logistic regression, applying the method to classify whether users would buy a product - or maybe click on an ad. The chapter was not very clear about what the data pertained to, it mentioned a lot about users clicking on ads in the preceding text however the dataset column was entitled :y_buy. Unfortunately the headers were not explained on the github readme or in the book. Nevertheless, let’s crack on.

Logistic Regression relies on the inverse logit function

P(t)=logit−1(t)=11+e−t=et1+et,

which maps values from the real line R to the interval [0,1]. We’ll only consider the binary case here, where our response variable/class ci=1 or ci=0. We start with P(ci|xi)=[logit−1(α+βTxi)]ci[1−logit−1(α+βTxi)](1−ci),

Training the model relies on estimating the parameters α and β. To do this we define the likelihood function L(Θ|X1,X2,…,Xn)=P(X|Θ)=P(X1|Θ)…P(Xn|Θ), where Θ=α,β and our users are independent. We then calculate the maximum likelihood estimator ΘMLE

ΘMLE=argmaxΘn∏i=1P(Xi|Θ).

To evaluate the model, I calculate the AUC of the ROC curve and used 10-fold cross-validation.

In the book, this exercise came with a large amount of R code that I translated to Julia. This included implementing the cross-validation, calculating the AUC, etc. I trained the models using the GLM library

mod = glm(f, train, Binomial(), LogitLink());

y_pred = StatsBase.predict(mod,test);

as well as using the MLJ library

logreg = @load LogisticClassifier pkg="MLJLinearModels";

logreg_mach = machine(logreg, X, categorical(y));

train, test = partition(eachindex(y), 0.65, shuffle=true, rng=1234);

MLJ.fit!(logreg_mach, rows=train);

One thing to take into accoun when using MLJ is that the data must be in the correct Scientific Type before training the model. In this example I had to coerce all of the integer values to be continuous and the label to be of type Multiclass. This can be done using

coerce!(df_mlj,:y_buy => Multiclass);

coerce!(df_mlj,Count => Continuous);

where df_mlj is the data frame containing the data. Implementing the code manually and using MLJ allowed me to understand what is happening ‘behind the scenes’ while ensuring I know how to use cutting edge libraries.

The classification results suggested an AUC of approximately 0.81 was achievable using a single predictor, and this increased to approximately 0.86 when introducing a small number of predictors. In the brief analysis I performed in the notebook it appeared that the :last_sv feature was the most important for achieving greater model performance. I did try calculate Pearsons correlation coefficient for each feature, however this did not provide a good estimate for which variables may be omitted. I’d like to explore the feature selection further in the future.